Texts painted on adjacent walls and on a hanging silk sheet tell brutal, no doubt authentic tales of self-afflicted abortion.įinley’s texts in these tableaux aren’t just angry. Above her head a bird is trapped inside a cage, from which cascade hundreds of interlocking coat hangers. On the floor nearby, a woman in a nightgown lies in rumpled bedclothes on a mattress. “The Women’s Room” uses a similar lineup of domestic furniture-this time dressing tables whose mirrors are scrawled with familiar statements of women’s unequal status in our culture. The texts are part political tract-wagging fingers and assigning blame-part anguished wail of heartfelt grief. Opposite, two texts are inscribed in gold paint on a black wall. Two are empty, with votive offerings in place of absent people. Two hold patients, while caring friends are seated by their sides. Nearby, another attendant stands next to an open hope chest filled with sand you can trace a name with your finger.Ī row of four beds lines one side of the room. At its dual entrances, attendants offer visitors flowers to weave into a lace curtain or ribbons to tie on a wrought-iron gate, both in memory of one who has died from AIDS. “The Memorial Room” is the more elaborate of the two. (So far, more than 400 have signed up to participate during the show’s run.) They also invite museum spectators to become participants in the drama-that is, to become active rather than passive viewers.

“The Women’s Room” and “The Memorial Room” are stage sets constructed in the galleries, and they incorporate “actors” drawn from among community volunteers.

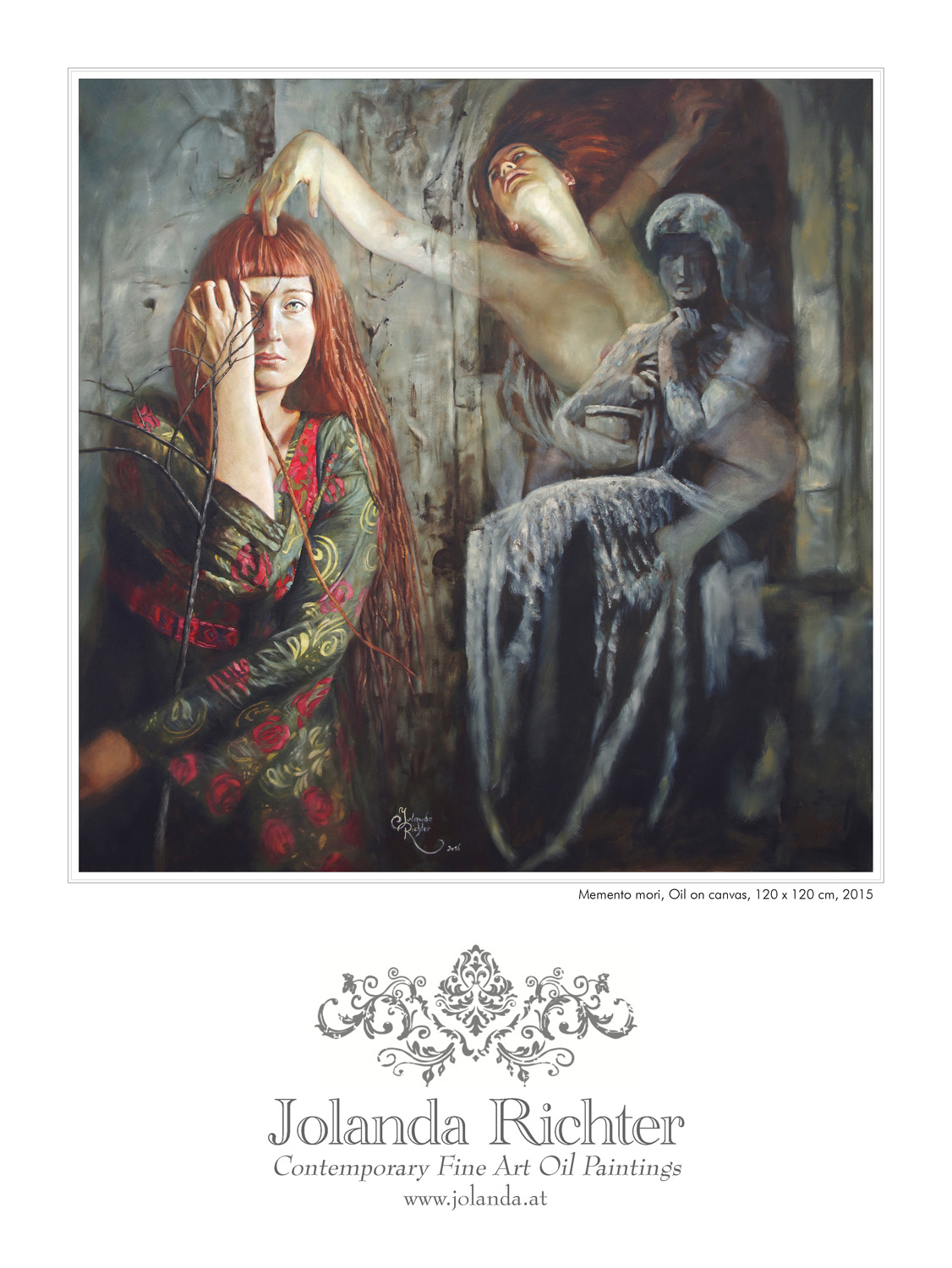

Art memento mori free#

“God is a Woman,” announces another mural, itself faced by the declaration on an opposite wall that “My God Is Homosexual (Love Your Neighbor as Yourself).” The gallery of murals is an antechamber to the rooms with Finley’s tableaux, and it creates a stark confrontation between her vocal assertion of the free play of ideas and the contradictory specter of blasphemy.įor an artist better known for performance work than for painting or installations, it’s not surprising that the theatrical dimension of agitprop is most plain in the two tableaux. “The Virgin Mary is Pro-choice,” declares the legend scrawled beneath a crudely painted wall image of the Madonna. She has been the target of phenomenal verbal abuse, and her art has been the subject of demeaning misrepresentation.įinley’s art is blunt and didactic. Both are bound up with complex questions of how certain people are marginalized in terms of social power, and of how that marginalized status can prove deadly.įinley is one of the so-called “NEA 4,”a group of artists currently suing the National Endowment for the Arts in the wake of alleged violations of their First Amendment freedoms. One is a woman’s right to choose in the matter of abortion, the other the nightmare of the AIDS epidemic. Their subjects aren’t just politically charged, they’re about the most volatile that could be imagined. “Memento Mori” includes several wall paintings and two tableaux vivants. They don’t exactly cancel each other out, but they do seem peculiarly flat. Still, the dual traditions coexist uneasily. Each is registered with an undeniable degree of commitment, and both contain elements of considerable power. Two venerable artistic traditions-one Modernist, one not-coincide in “Memento Mori,” Karen Finley’s ambitious installation at the Museum of Contemporary Art.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)